“You don’t have a home until you leave it.” – James Baldwin

I left New Orleans just after the start of the new year in 2018. It wasn’t the first time I left, nor the furthest from home I’d gone, but it felt different this time, more permanent. Unlike when I moved to Ethiopia in 2009, this time I was capital L leaving, with no plans to return.

And I haven’t, not to live, but where I thought I was starting new in another part of the country – Seattle, Washington, the Pacific Northwest, which may as well have been a foreign country for as far and different as it seemed – turned out to be the first stop in a series of cross country moves. From Washington State to Connecticut and now here, Oakland, California. All places I never imagined living.

What’s surprised me most in leaving is the lingering feelings of guilt and shame. Maybe it happens everywhere, but New Orleans is a place where people take pride not only in their roots but in their rootedness. “I’m never leaving,” folks say, stretching out ‘never’ to express their indignation at the very thought of it – leaving.

Growing up, the concept of evacuating for a hurricane was mostly foreign. I didn’t know anybody who did that. Staying home, sweating it out without electricity, trudging through ankle and knee deep water to check on your neighborhood, it was just what we did.

The tone has changed a bit since Hurricane Katrina and all the changes in the city that followed, this idea introduced of New Orleans as “a blank slate” for new possibilities, a coded term for gentrification. Still the pulse I get through the long wires of connection (Facebook, mostly) is folks being fed up, but staying put.

“It ain’t where you're from, it’s where you’re at.” – Yasiin Bey (Mos Def)

In a moment of longing, that song came to me but I rejected it. Maybe I was living in Connecticut at the time. That could definitely explain it. No shade to New England or New Englanders (y’all have a gorgeous fall), but coming from where I was coming from, that place was hard. I’ve never felt more lonely in all my life. (Weekend train trips to New York City – Brooklyn, more specifically – was a balm.)

This is my sixth year away from home. (I counted on my fingers to be sure, then I counted again.) I’m beginning to reckon with the ways I cling to culture and identity, and how that might be holding me back. Did I say reckon with? Okay, at least acknowledge.

When I meet people, I always tell them I’m from New Orleans. That’s just a fact. But sometimes it’s a crutch. Somebody might tell me about such-and-such place I might want to check out. They’ll start to give me directions, and I’ll start to tune them out. “Well, I’m not from here,” I’ll say, dismissing their suggestion. I’ll catch myself and wonder, why do I do that? Okay, there’s my real trepidation of driving around the Bay Area with its unexpected hills and complicated streets. But it's more than that.

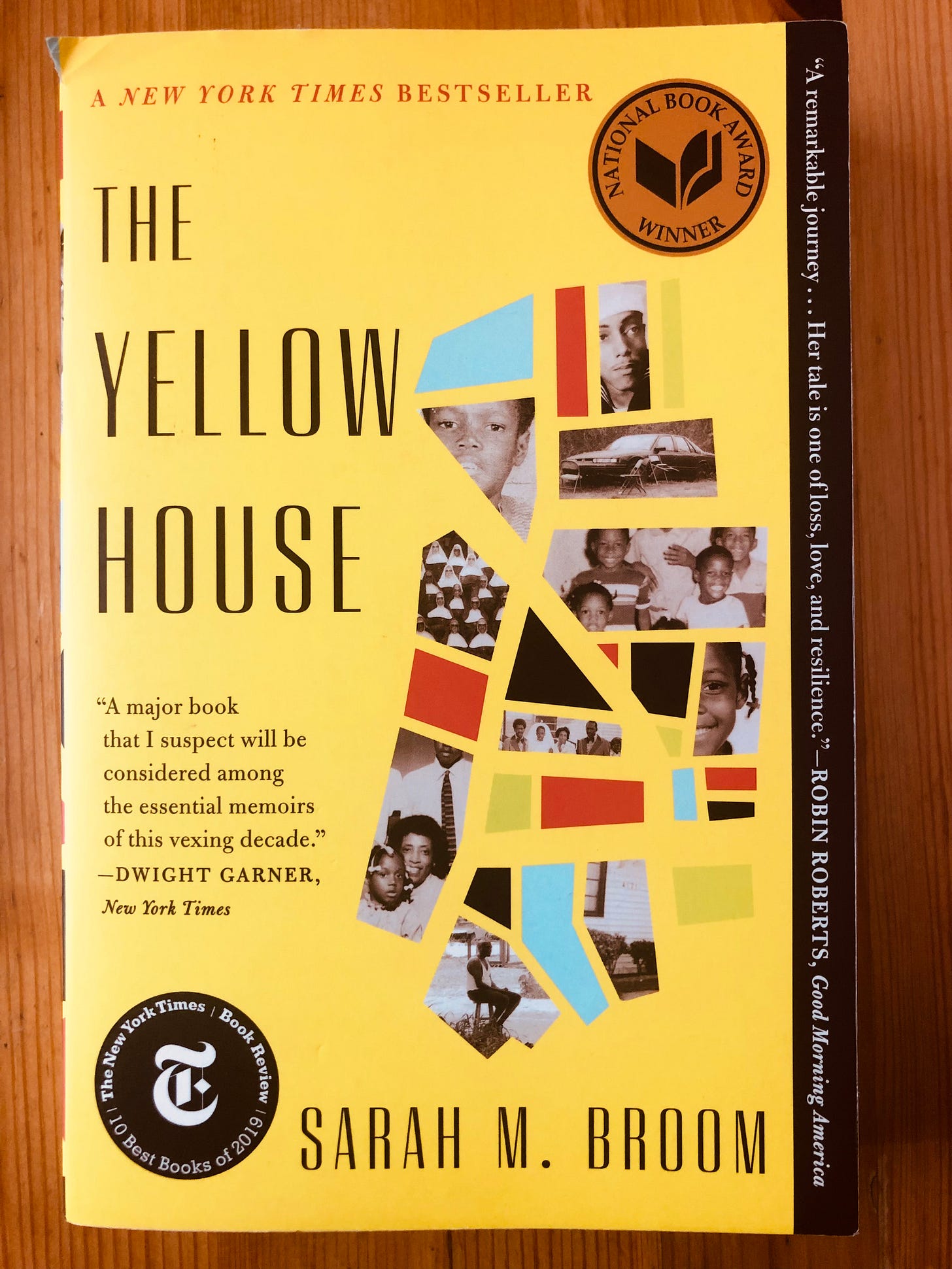

The Yellow House by Sarah Broom is my favorite book about New Orleans. Reading that book was the first time I read anything about my homeland in which I actually saw myself, my family, my childhood, my neighborhood and community. In telling the story of her family, Broom tells the story of Black New Orleans. What I admire most about her writing is her journalistic approach. It’s not a book written about us, it’s a book written to us. And in writing to us, she asks some tough questions, and forces us to take a mirror to ourselves.

Why are we so fixated on authenticity? Why do we shout down anything that smells like criticism, even from our own? Broom asks, if not Black people, the backbone of “much of what is great and praised about the city,” then who has the right to tell the story of New Orleans?

Broom, like me, is a native New Orleanian with deep roots who moved away and lives elsewhere. I sense her own feelings of guilt and defensiveness of her choice to move away. But she does what good writers do, what deep thinkers do, pushing herself and her readers to interrogate the stories, and myths, they insist define them.

One question she asks that has stayed with me is, “When you come from a mythologized place, as I do, who are you in that story?”

To riff off prolific New Orleans journalist Lolis Eric Elie, New Orleans is a city of character, but when we buy into the mythology and become performative, we risk becoming caricature. The only way to challenge that mythology is to tell all our stories and be honest about what is harming us, even, and especially, if that harm is coming from “the culture.”

To call any place other than New Orleans home feels like a betrayal. I can’t claim the Bay Area because I don’t feel its history in me like I feel New Orleans’ – although I do see traces of it in Oakland, where people from Louisiana historically migrated. (How’s that for a spooky connection?)

Home is where my roots are. The oldest ancestors I’ve been able to trace came against their will from West Africa and survived to stand on land that came to be called Louisiana. My family’s history in New Orleans is as old as the city itself. I visited the plantation near Cane River where my sixth great grandmother was enslaved and fought her complicated way to freedom. I felt a terrible sense of unease there and couldn’t wait to leave, but I’m grateful I was able to stand on that land.

What hurts though is when I ask myself if I want to go back home, the answer is a hesitant, whispered no. Not really. Maybe. Sometimes… I want to be there but don’t want to be there, for reasons I can’t even bring my fingers to type – the pull of authenticity i.e. never criticizing, still holds me.

It’s like wanting to feel the weight of a blanket while I sleep, but not wanting all its heat. Too much to embrace, but near enough to grab when I get cold. Cold, hot. Cold, hot. On, off. On, off. Just stay close, please.

What a beautiful essay and love letter to New Orleans! I loved reading it, and the ending with the blanket metaphor is powerful.

I like reading other migrants' views on home, and yours made me realize mine is quite the opposite. I grew up in Romania, a Communist country in the 80s, and all I was taught was to leave as soon as possible. To leave for a chance at a better life, leaving as an escape. I don't feel the roots as strongly as you describe. Actually, I feel rootless. I have lived in beautiful places from Miami to Barcelona, Spain, but I always feel like I'm renting the space where I make temporary homes, I'm renting the geography. It's lovely to read a different perspective of the migrant's journey.

As a lifelong Houstonian I've always been fascinated by the culture and people of New Orleans. One of my best friends growing up was part of the Orleanian diaspora that was forced out after Hurricane Katrina. I've visited many times, there's this distinct romance about the city and it's people that I really cannot get enough of. Thanks for sharing your story!